| Heterochrony in cavusgnathid conodonts |

|

|

are the "Granton Animals" paedomorphic?

Mark A. Purnell

University of Leicester |

|

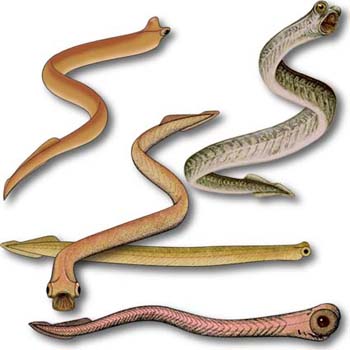

Recent reconstructions of the conodont body, all approximately

4 cm long. a, from Aldridge and Purnell3; b, from Discover5; c, from Purnell et al.6; d, from Purnell7; e, from Aldridge et al.2 Recent reconstructions of the conodont body, all approximately

4 cm long. a, from Aldridge and Purnell3; b, from Discover5; c, from Purnell et al.6; d, from Purnell7; e, from Aldridge et al.2

|

|

|

|

| The discovery and interpretation of the Scottish fossils preserving

traces of conodont soft tissues1, 2 have revolutionized many aspects of the study of conodonts. After

more than 100 years of uncertainty and speculation, we finally

have some understanding of the biology and ecology of conodonts.

Reconstructions of the conodont body are an important component

of this new conceptual framework. Not only do these reconstructions

satisfy our basic curiosity about a group of enigmatic, extinct

organisms, they are a powerful influence on developing concepts

of conodonts as living animals, and reconstructions themselves

become the subject of biological interpretation and speculation. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Natural assemblages of cavusgnathid conodonts. Larger images can

be viewed by clicking on these smaller copies |

|

|

| Almost all recent reconstructions of conodonts (see above) are

based primarily on the best known and best preserved material:

the Carboniferous cavusgnathids (Clydagnathus windsorensis) from Granton, Scotland. But how well do these few specimens

represent conodonts as a whole? |

|

| Analysis of apparatus growth in cavusgnathid conodonts (see plot

above) using measurements of elements in the Granton specimens

and bedding plane assemblages from the Carboniferous of Montana

(see photographic images above plot), provides strong support

for the hypothesis that Clydagnathus windsorensis is progenetic (i.e. paedomorphic). This does not call into question

any of the key anatomical attributes of conodonts, or their assignment

to the vertebrates3. Neither does it indicate that the Granton conodonts are larval

forms (contra ref. 4). It does suggest, however, that some details

and proportions of reconstructed animals may reflect juvenile

morphology rather than that of a typical adult conodont, whatever

that may be (see plot). |

|

|

|

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. Briggs, D. E. G., Clarkson, E. N. K., and Aldridge, R. J.,

1983. The conodont animal. Lethaia, 16, 1-14.

2. Aldridge, R. J., Briggs, D. E. G., Smith, M. P., Clarkson,

E. N. K., and Clark, N. D. L., 1993. The anatomy of conodonts.

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series

B, 340, 405-421.

3. Aldridge, R. J., and Purnell, M. A., 1996. The conodont controversies.

Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 11, 463-468.

4. Forey, P., and Janvier, P., 1994. Evolution of the early vertebrates.

American Scientist, 82, 554-565.

5. Picture blood on its teeth. Discover, 17, 45 (1996).

6. Purnell, M. A., Aldridge, R. J., Donoghue, P. C. J. & Gabbott,

S. E. 1995: Conodonts and the first vertebrates. Endeavour 19, 20-27.

7. Purnell, M. A. 1995: Large eyes and vision in conodonts. Lethaia 28, 187-188.

8. Element dimensions are taken from bedding plane assemblages

of Cavusgnathus from the middle Carboniferous of Montana, USA, and from exceptionally

preserved Clydagnathus windsorensis from the Lower Carboniferous of Scotland. Curves represent the

power function or allometric equation y=axb and were fitted to Cavusgnathus data only, using linear regression. Dashed line extrapolates

the Pb element curve beyond the Cavusgnathus data. |